18 mars 2022 - 14 h 00 min - 17 h 00 min

Séance commune avec le séminaire Humanités environnementales

Antoine Traisnel (University of Michigan) présentera une communication intitulée “In the Doldrums: Plastic and the Sea”

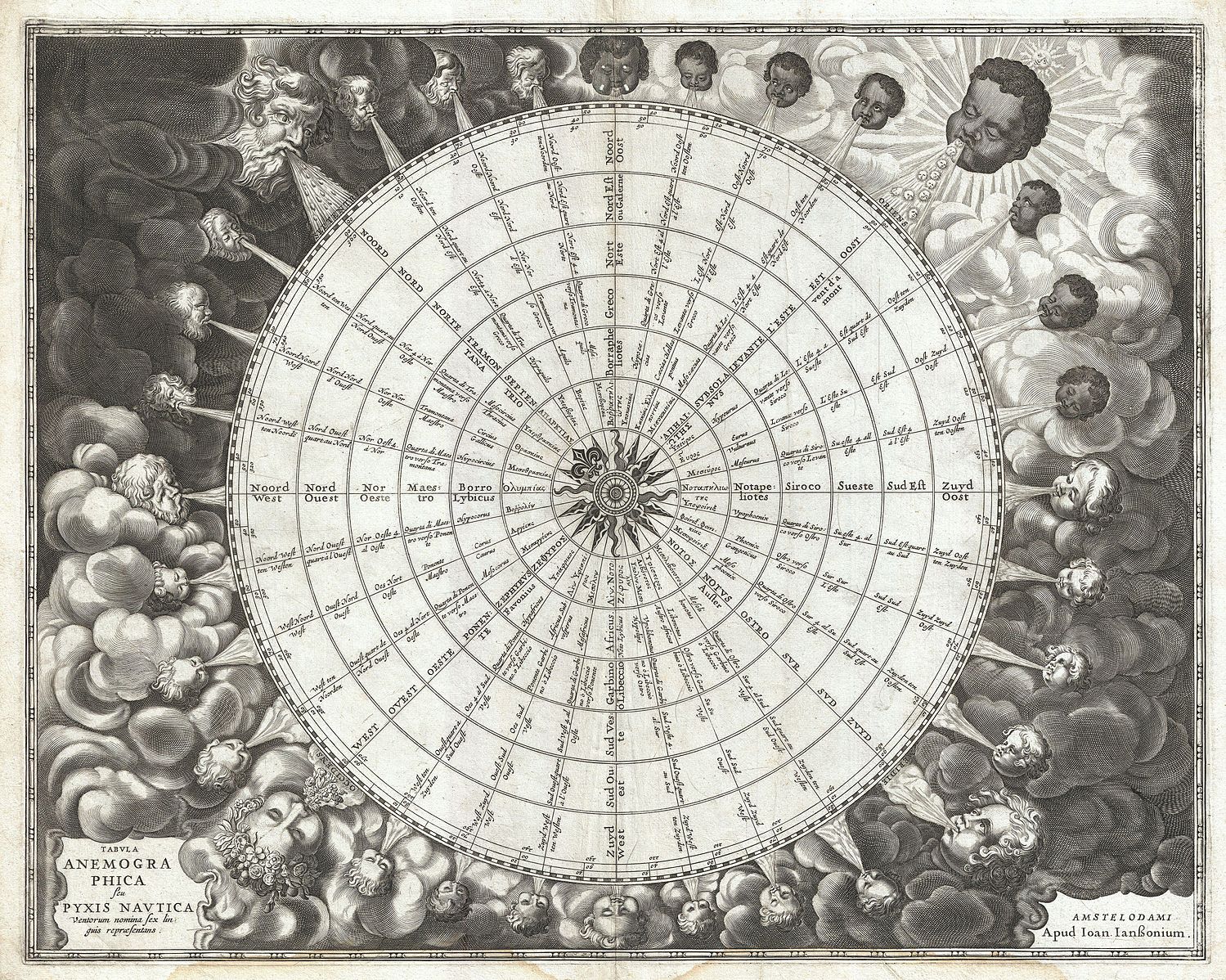

In this creative-critical essay, co-written with Thangam Ravindranathan (Brown University), we reflect on the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an area of marine debris spanning 1.6 million kilometers in the North Pacific Ocean. The 87,000 metric tons of non-biodegradable plastic bits and particles gathering in this span of ocean—due to a particular confluence of marine currents in the subtropical convergence zone and the “trapping” of litter in the stable center of the resulting vortex—occupies today the exact zones that used to be known in the Age of Sail as the doldrums—the “dead calm” described by sailors and writers, most famously in Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner, some of Melville’s writings and Lévi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques. In the doldrums, due to the complete absence of wind for weeks at a time, ships would be stranded, both space and time seemingly at a standstill. If technologies for “annihilating space and time” (Marx), and specifically fossil-fuel-powered motorized speed, took humans decidedly out of the doldrums, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch stands as a testament to the fact that no speed is fast enough for a metaphor to transcend its own material remainder. From the fuel that powered the ships and factories and fast urban lives of industrial modernity came also petrochemicals, notably plastic, that will not biodegrade—or “go away”—within actionable time. The tons of plastic in the North Pacific gather as the indelible waste of mass consumer culture and pose an extremely toxic danger to marine ecosystems. This talk, experimenting with the formal conceit of an interstitial chapter to Moby Dick (where the Pequod finds itself mired in a sea of debris), meditates on the impeccable if submerged chiasmus-like operations linking dematerialization and matter, the metaphorical and the earthly, transcendence and disposal, that work at the heart of capitalist modernity, and that make the Great Pacific Garbage Patch a haunting “hyper-object” (Morton) of our space-time.

Antoine Traisnel is Associate Professor of Comparative Literature and English at the University of Michigan. He holds doctorates in American Literature from Université Lille 3 (2009) and Comparative Literature from Brown University (2013). His published books, essays, and translations span the fields of American, French, and German Literature; critical and literary theory; biopolitics and ecocriticism. He is author of: Capture: American Pursuits and the Making of a New Animal Condition (U Minnesota Press, 2020); Donner le change: L’impensé animal (Hermann, 2016), co-written with Thangam Ravindranathan; Hawthorne: Blasted Allegories (Aux Forges de Vulcain, 2015). He is the translator of Sheppard Lee (Aux Forges de Vulcain, 2017). His recent and current research examines cultural and literary works through the lens of biocapitalism and extinction. It explores the historical, aesthetic, and philosophical footholds of the administration of life, concerns made all the more urgent in our present of escalating necropolitical and environmental crises. He co-leads the Critical Futures Project, a research collective that explores theoretical methods for addressing the new urgency of climate change under digital and racial capitalism.

Michael Jonik (Univ. of Sussex) présentera une communication intitulée “A Dictionary of the Indian Languages”: Thoreau’s Ecopoetic Ethnobotany.” Antoine Traisnel (U. of Michigan) sera discutant.

At the end of his Maine Woods, Thoreau adds a brief “Appendix” containing plant and animal names (including Latin nomenclature and common English names), advice for those who would “outfit” an excursion upriver in Maine, and a “List of Indian Words.” The latter list relates primarily to place names or to geographical or topographical features of the Penobscot valley, and signals Thoreau’s diverse yet intense interests in cartography and toponymy, geology and hydrodynamics, botany and zoology, anthropology and Colonial history, and, indeed, philology and poetics. Thoreau had compiled this multilingual list of words from the Abenaki language from a variety of sources, including Sébastien Rasles’s A Dictionary of the Abnaki Language, in North America (which translated Abenaki into French), Willamson’s History of Maine, and words he learned directly from his Penobscot guides (especially Joe Polis) during his three excursions recounted in “Ktaadn,” “Chesuncook,” and “The Allegash and the East Branch.” In this presentation, I explore his increasing intimacy with Native American understandings of the environment, epistemologies, cultures and lifeways: an eco-political phronesis outside white liberal knowledge structures, or what he calls in “Walking” a “more perfect Indian wisdom.” He celebrates this new intimacy with the natural world that Native American words offer him in his journal on March 5, 1858: “A dictionary of the Indian Languages reveals another and wholly new life to us. … It reveals to me a life within a life” (March 5, 1858). Building on such moments, this paper investigates the implications of Thoreau’s inclusion of Indigenous languages in his writings, especially his use of Abenaki words The Maine Woods, as well as instances from his journals and selections from his “Indian Notebooks.” My contention here is that Thoreau’s increasingly sensitive inclusion of Abenaki words across his three excursions recounted in The Maine Woods indicates a shift away from a Romantic tropology of Native Americans as primitive and vanquished in his thinking. Instead, Thoreau uses words as a means to engage a living Indigenous population and to discern a more vibrant and intimate relational ontology of plant and animal life previously foreclosed to him. At the same time, Thoreau’s interleaving of Indigenous languages into his writing does not happen separately from that of the Latin taxa or French words that often appear in his texts, but rather creates a dynamic, multilingual palimpsest of his ecopoetical experiences.

Michael Jonik is Senior Lecturer in English and American Literature (English and American Studies), Director of Research and Knowledge Exchange (School of Media, Arts and Humanities) at Sussex University. Michael Jonik teaches American literature and contemporary critical theory at the University of Sussex. He recently published Herman Melville and the Politics of the Inhuman (Cambridge University Press, 2018), and he writes on pre-1900 American literature, continental philosophy, and the history of science. Michael was previously a postdoctoral fellow at the Cornell University Society for the Humanities. He has won research grants from the Spanish government, the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council, and the Leverhulme Trust, and was a fellow at the Institut d’études avancées de Paris. He is founding member of The British Association of Nineteenth-Century Americanists (BrANCA), and Reviews and Special Issues editor for the journal Textual Practice.

Lien zoom @ https://a19.hypotheses.org/

- Vendredi 9 avril, 14h-16h : Hélène VALANCE (Université de Franche Comté) : “Inconséquences historiques : Les visions anachroniques de Susan Fenimore Cooper dans ‘A Dissolving View’”