First quarto of Venus and Adonis (1593) – British Library

‘Long may they kiss each other, for this cure!

O, never let their crimson liveries wear!

And as they last, their verdure still endure,

To drive infection from the dangerous year!

That the star-gazers, having writ on death,

May say, the plague is banish’d by thy breath.’ (Venus and Adonis, 526-31)

“What did you do over the lockdown period?” The question gets asked and is likely to get asked again over the coming months, with the ups and downs of a dragging sanitary crisis affecting us all. Some panic at the thought of having under-achieved during this period, others overdid it out of the same sense of panic or simply to keep their minds focused on something positive. Across academia, we generally struggled with teaching and research duties, adjusting to new circumstances on a trial-and-error basis. In the process, many of us in humanities departments looked with a fresh eye at authors from the past on whom we have been working for so long, feeling a sense of empathy we had never experienced before, wondering: How did they cope with times of pandemic? How much do their writings owe to lockdowns?

COVID-inspired articles by some of the best-known names in Shakespearean studies, from Stephen Greenblatt1 to Emma Smith,2 have drawn their readers’ attentions to the analogy between Elizabethan plague pandemics and the current crisis, making Shakespeare our contemporary in new and unexpected ways. We learn from them how much “epidemic disease was a feature of Shakespeare’s life,”3 from the sinister mention hic incipit pestis (here begins the plague) in the parish register of Stratford-upon-Avon a couple of months after his birth in 1564 to the long periods of theatre closure due to plague quarantine throughout his years of activity. Hovering on the fringes of the plot of Romeo and Juliet, plague is what prevents the messenger carrying Friar Laurence’s letter from reaching Romeo in his Mantuan exile, making the quarantine the direct cause of the lovers’ tragedy, the “plague upon your houses” of Mercutio’s proleptic last words. More than just a plot device, plague may also have been the circumstance locking up the playwright long enough for him to produce later in his career some of his darkest tragedies, from Macbeth to King Lear. As Andrew Dickson puts it humorously, “if you weren’t panicky enough about how little you’ve achieved recently, this is surely a way to feel worse.”4

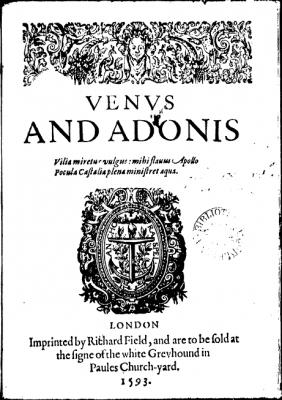

Most of the COVID-inspired pieces mentioned above are directed at the general public, which implies that they deal primarily or exclusively with Shakespeare the writer of plays. In so doing, they leave aside his other great achievement in times of plague, that is to say the innovative narrative poems, Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece, composed during the plague lockdowns of 1592–3, as the furloughed dramatist badly needed patronage and alternative sources of income. Two of “the most intensely erotic poems of a decade in which much of the best writing was erotic,” they possibly owe as much to the urge of living life to the full against a backdrop of illness and death as they famously do to the Elizabethan vogue of Ovid-inspired erotica launched by Arthur Golding’s translation.5 Venus and Adonis, the very first work printed under Shakespeare’s name, strikes us as possibly “the most purely mythological” of his works.6 As such, it could appear an escapist fantasy, shunning topicality in its choice of plot, turning its back altogether on the pandemic as so many of us did in lockdown, howbeit in less grand style, some taking to gardening and baking bread, others to learning yoga or binge-watching TV series.

And yet, if undoubtedly “documentary realism was not Shakespeare’s style,”7 the shadow of the epidemic disease haunts over this seemingly not plague-related story of unrequited love between an eager goddess and a handsome young man resisting her. The disease briefly shows its face in the most unexpected place, like a return of the repressed, in a climactic stanza devoted to a kiss granted by the otherwise cold Adonis to revive a fainting Venus. Fleeting though the moment is, the stanza captures much of the essence of the “dangerous year” of the work’s composition.

Over the short span of just six lines, this vignette of the plague year evokes the miasmas which Elizabethans believed to be the cause of the contagion, dispelling them with the sweet breath of the delicious youth. The “verdure” of his lips, referring either to their freshness or the nascent duvet of his manhood, merges in this evocation with the fragrant herbs carried or burned by Londoners in the hope of fighting the contagion. Redeeming the green colour of putrefaction, the conceit makes it one and the same with the wholesome red of youthful lips lending themselves to a kiss, beyond any sense of our recommended “social distancing” in epidemic times. Making the prognostications of “star-gazers” lie, the hero’s kiss and the poet’s stanza overcome the malady for both the fainting heroine and the modern reader stuck home in self-isolation.

Reconnecting with a fellow Stratford man, printer Richard Field who published the 1593 quarto of Venus and Adonis, the Bard may have borrowed from his shop, either during plague time or between two outbreaks, some of the major sources of many of his plots, from Golding’s translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses to North’s translation of Plutarch’s Lives and Holinshed’s Chronicles.8 A model of resourcefulness to emulate, perhaps, next time we think lack of access to research material in times of pandemic is stifling our creativity on top of complicating lives and jobs. And how about starting right now, by contributing to a blog on medical humanities like this one?

Professor of Early Modern Studies

Université de Paris, LARCA, CNRS, F-75013 Paris, France

1 Stephen Greenblatt, “What Shakespeare actually wrote about the plague,” The New Yorker, 7 May 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/what-shakespeare-actually-wrote-about-the-plague

2 Emma Smith, “What Shakespeare teaches us about living with pandemics,” The New York Times, 28 March 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/28/opinion/coronavirus-shakespeare.html

3 Paul Yachnin, “After the plague, Shakespeare imagined a world saved from poison, slander and the evil eye,” The Conversation, 5 April 2020. https://theconversation.com/after-the-plague-shakespeare-imagined-a-world-saved-from-poison-slander-and-the-evil-eye-134608

4 Andrew Dickson, “Shakespeare in lockdown: did he write King Lear in plague quarantine?”, The Guardian, 22 March 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2020/mar/22/shakespeare-in-lockdown-did-he-write-king-lear-in-plague-quarantine

5 Lois Potter, The Life of William Shakespeare: A Critical Biography, Oxford, Blackwell, 2012, p. 107.

6 Frank O’Toole, “Shaking up Shakespeare,” The Irish Times, 29 October 1996.

7 Smith, op. cit.

8 James Shapiro, A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare: 1599, New York, Harper Collins, 2005, p. 133.