The Covid-19 pandemic is at the heart of all our public discussions. Was wearing masks indispensable from the start ? Should doctors use chloroquine to treat patients ? In France, the latter dispute pitted doctors against doctors, mainly in the early stages of the disease. The battle was not simply fought discreetly in hospital staff meeting rooms, but very openly in the public sphere as medical experts voiced their differing views during prime time television shows.1 And new issues arise : should health-care workers receive extra bonuses, and who counts as a front-line worker ? In the late eighteenth-century, similar controversies could be played out in the print sphere, not in television studios, with various parties resorting to published pamphlets in order to express their contrasting opinions.

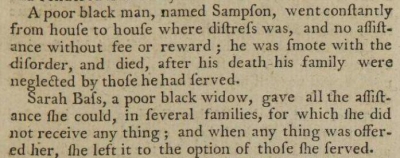

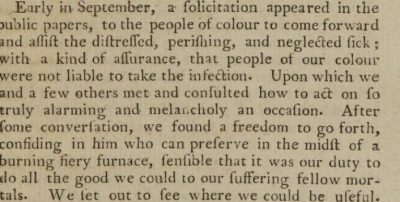

A good case in point is the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia, then the federal capital of the United States with about 50, 000 inhabitants. This epidemic generated several controversies and an accompaying number of publications. In his narrative of the epidemic, prominent Philadelphia journalist, Mathew Carey, offended leaders of the newly-organized African-American community, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, by suggesting they had overcharged for their services as nurses and grave-diggers during the three-month crisis (September_November).2 Allen and Jones countered by explaining that the black community had been self-sacrificing in their devotion to the white community, especially as Dr. Benjamin Rush, a Philadelphia worthy and signer of the Declaration of Independence, had asked them to come forward and help on the mistaken assumption that they were immune to the disease.3 Who counted as a front-line worker and how they should be rewarded was already a preoccupation.

Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, A Narrative Of the Proceedings of the Coloured People during the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia in the Year 1793 : and A Refutation of some Censures, Thrown upon them in some late Publications (Philadelphia: William W. Woodward, 1794), p.11; pA2.

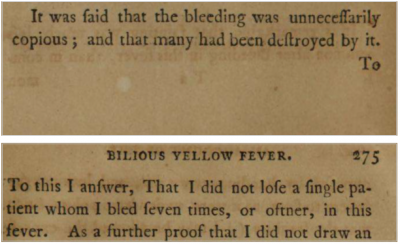

What Rush taught African-American nurses was to bleed patients, as he considered blood-letting as the only efficient cure. His unreasonable, and even frantic, reliance on bleeding, led to quarrels with other Philadelphia doctors, and to his eviction from the Philadelphia College of Physicians. Rush published his defense in 1794 in a 300-page pamphlet that includes detailed descriptions of the onslaught and various stages of the disease.4 Other physicians’s reputation fared much better as their treatment was seen as more successful. This was the case of French Dr. Jean Devèze, who oversaw Bush Hill hospital during the epidemic. Bush Hill had been established by the city authorities with the express purpose of taking in the yellow fever victims.

Rush B. Account of the Bilious Remitting Yellow Fever as It Appeared in the City of Philadelphia in the Year 1793. Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson; 1794. pp. 274-75

Focusing on Devèze, a refugee French doctor from Le Cap, in Saint-Domingue (Cap Français then), makes it possible to place the yellow fever epidemic in its Atlantic context in the age of revolutions. While the controversy between Carey and the black community highlights the rising discrimination which a well-meaning black community suffered from in the early American republic, the presence of Devèze in Philadelphia reminds us of the very particular role which the United States and its eastern-board cities played in the revolutionary wars then starting in the Atlantic.

France declared war on Britain on February 1, 1793. The United States long hesitated but proclaimed neutrality late in the spring of 1793, thus remaining open to both French and British ships. Meanwhile Saint-Domingue, a wealthy French slave colony which had many commercial relationships with Philadelphia and other eastern-board cities, was ravaged by a major slave insurrection and civil war between groups of whites. In June 1793, the city of Le Cap was set on fire and thousands of refugees fled to Philadelphia and other cities in the United States, where they would become fixtures in the coming decade. Obviously they could not go back to France as long as the Royal Navy dominated the seas.

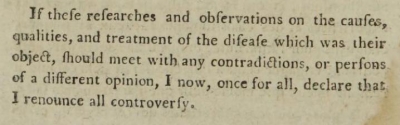

Devèze was part of the wave of refugees who poured into Philadelphia in August 1793, and may have brought the deadly yellow fever-carrying mosquito with them, although he himself rejected this possibility. Devèze did not believe in contagion but in the corruption of air. Philadelphia, with its inner-city burial grounds, its tanneries and many areas of stagnant waters, seemed to him a perfect breeding-gound for an epidemic. Devèze’s treatment, while not excluding blood-letting, stressed ingestion of lemonade and cold water, among other healthy liquids. As a conclusion to his report on the epidemic (he denied the report was part of a controversy in the early pages), Devèze recommended that burial-grounds be moved outside the city, ditches regularly cleaned and healthy water brought in from outside the city (very much like washing one’s hands today, and other barrier measures).5

Jean Deveze, An Enquiry into, and Observations upon the Causes and Effects of the Epidemic Disease which Raged in Philadelphia from the Month of August till towards the Middle of December, 1793 (Philadelphia: Parent, 1794) p. vi; p. 12; p. 20; p.38.

Unlike Rush, whose medical star waned after the epidemic, Devèze’s involvement in the yellow fever epidemic led to his being elected as a member of the prestigious American Philosophical Society in 1796. But we know little about him beyond that and his treaty on the yellow fever. He does not appear in discussions on the French refugees, slavery in saint-Domingue and related issues. Yet his prophylactic ideas lived on. Most particularly, his insistence on burial-grounds being moved outside cities was probably shared by many as major cities in the United States started building rural cemeteries in the early 19th century. Somehow those early controversies paved the way for our modern discussions on the pandemic.

Université de Paris, LARCA, CNRS, F-75013 Paris, France

1www.bfmtv.com/mediaplayer/video/didier-raoult-parle-sur-bfmtv-revoir-l-entretien-en-integralite-1243716.html

2 Mathew Carey, A Short Account of the Malignant Fever Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia (Philadelphia : Third Edition, November 30, 1793).

3 Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, A Narrative Of the Proceedings of the Coloured People during the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia in the Year 1793 : and A Refutation of some Censures, Thrown upon them in some late Publications (Philadelphia: William W. Woodward, 1794)

4 Benjamin Rush, An Account of the Bilious Remitting Yellow Fever, as it Appeared in the City of Philadelphia, in the Year 1793 (Philadelphia : Thomas Dobson, 1794).

5 Jean Deveze, An Enquiry into, and Observations upon the Causes and Effects of the Epidemic Disease which Raged in Philadelphia from the Month of August till towards the Middle of December, 1793 (Philadelphia: Parent, 1794).